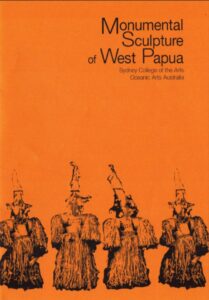

Exhibition: The Monumental Sculpture of West Papua Sydney College of the Arts Sydney 2000

| Collection No. | The Monumental Sculpture of West Papua |

|---|---|

| Size |

Exhibition: The Monumental Sculpture of West Papua Sydney College of the Arts Sydney 2000: The Todd Barlin Collection of New Guinea Art

This groundbreaking exhibition of The Monumental Sculpture of West Papua was part of the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games Arts Festival featuring Arts of the Pacific Islands & the Island of New Guinea

The Sydney College of the Arts part the University of Sydney welcomed me to do this superb exhibition as part of the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games Arts Festival, they offered a large and unique space & technical support to display these monumental sculptures, and they also offered the chance for large coloured walls that made the artworks shine as seen in the photos below. Todd gave several talks about the collection of artworks and his time spent living with the Asmat & Kamoro ( Mimika) people. The photos explain the beauty of this exhibition.

The main Asmat creation myth is about the creator Fumeripitjs who was lonely so he carved figures from wood and then he made a drum, when he played the drum the carved wood figures came to life and that is how the first Asmat people were created. For the Asmat the connection between trees and people and the forest is profound.

The exhibition had a large wall of Asmat Mbis Ancestor Poles & Komoro (Mimika) Mbitoro Ancestor Poles, a group of Ancestral House Posts from the inside of an Asmat Men’s Ceremonial House or Jeu, there was also a large group of Asmat & Mimika Dance Costumes that were used in funerary ceremonies. There were Todd’s field photos & information throughout the exhibition. The exhibition was possible through the assistance of Tom Arthur & Colin Winter & Chris Boylan.

At the close of the exhibition, I invited several Australian Museums & Art Galleries to choose the large-scale sculptures as gifts for their public collections some of which are now on display in The South Australian Museum & The Australian Museum in Sydney.

For this exhibition, there was an essay Asmat Art of Irian Jaya West New Guinea by Todd Barlin in Arts Asia Pacific Magazine Issue 28 October 2000

Asmat art of southern lrian Jaya has been widely exhibited around the world, including in the United States and Europe.

In Sydney in September 2000, as part of the Olympic Arts Festival, many will have a chance to see the beauty and richness of Asmat art when ‘The Monumental Sculpture of the Asmat opens at the Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney.

Also, on view at the same venue are The Shields of Oceania’, an exhibition of shields from Melanesia; and ‘Hokianga’, an exhibition by New Zealand photographer Ross T Smith.

Monumental Sculpture of the Asmat, presented by Oceanic Arts Australia, will bring the foyer of the Sydney College of the Arts alive. Todd Barlin owner of Oceanic Arts Australia, had had a long association with Asmat artists having spent extensive periods in the Asmat region collecting art and documenting ceremonial life, and has sponsored several international exhibitions of Asmat art, including a major exhibition at the National Museum of African & Oceanic Art in Paris in 1996 and another at the National Museum of New Caledonia in 1998.

The Shields of Oceania showcases excellent examples of my Asmat shield collection which are one of the most beautiful forms of Asmat art. Their shape and design motifs are widely varied and examples of the four Asmat regional styles will be exhibited.

The most exciting aspect of planning exhibitions is documenting, through field photographs, the artists and artworks in situ. This process creates a context for the works, illustrating how they have been made and are used. A lack of connection with acknowledgment of the artists in many exhibitions of Oceanic art sadly makes the artists seem anonymous.

Much has been written about the influence of ritual headhunting on Asmat art. It is true that many of the symbols used in Asmat art arc associated with headhunting, but it is perhaps the Western world’s fascination with ‘gruesome practices’ that has created a focus on this aspect of Asmat’s past ritual life. The complex spiritual beliefs of the Asmat are integral to their expression of art and ceremony. They believe that by honouring their ancestors through correct and continuing rituals, harmony and balance are maintained. Their religious practice includes ritual carving for ceremonies, dance, song, and storytelling. The myth of Asmat’s creation by the creator Fumeripitsj is integral to their ritual woodcarving:

“Fumeripitsj went into the jungle and built a feast house, but was lonely. He cut down trees and carved figures, each with a head and a body and with arms and legs. Some were male and some female. He placed them inside the feast house, but he was still lonely. So, he cut down a tree, hollowed out a section of log, and carved a drum. He covered one end with lizard skin, gluing it there with lime and some of his own blood and tied it with rattan. When Fumeripitsj beat on the drum, the figures began to move, awkwardly at first, but then their joints loosened, and they began to dance and sing in a normal way. Thus, the first Asmat came into being “

The Asmat have been quick to see similarities between Christian teachings and their own spiritual concepts, and Christian beliefs have been intertwined with their traditional beliefs to produce a new era of spiritual expression through their art.

Several churches in the Asmat area are adorned with beautiful ritual carvings that symbolize Asmat’s belief in Christianity. The Asmat have retained much of their traditional culture thanks to the encouragement of Bishop Alphonse Sowada (1933- 2014) and the Catholic Fathers of the Crosier Mission in Agats, the main administrative town. This dedicated group of priests has encouraged the Asmat to retain pride in their traditional culture. In the 1970s the Crosier Mission set up a small museum that houses a fine collection of Asmat art, as well as records of the Asmat’s oral history and ceremonial life.

Monumental Sculpture of the Asmat will include numerous monumental sculptures by Asmat artists, including Mbis Ancestor Poles, architectural house posts from a jeu, or men’s house; wuramon, or Soul Canoes and Jipae Dance Costumes, all of these artworks are representations of deceased ancestors.

The Mbis feast is a ceremony associated with the ritual of headhunting and the initiation of young men. The feast is still performed today and, although headhunting has long ceased, it remains an important aspect of honoring ancestors and teaching the young their responsibilities to their ancestors. House Posts which are made for the men’s house are carvings of human figures representing each family’s ancestors.

Each family has its own place, with a fire pit and a House Post erected in the Men’s Ceremonial House.

Wuramon or Soul Canoes are part of an initiation ceremony for young men and are made in only a few villages in northwest Asmat. The soul canoe, which can be up to twelve meters in length, is carved in the shape of a canoe and is filled with Ancestor Figures & totemic animals, a special house with a central beam in the shape of a crocodile head is built for the initiates, who are secluded there for several weeks before the ceremony, which includes dancing and singing and culminates in the scarification of the young men.

Jipae Dance Costumes are made in both central and northwest Asmat, they are used to drive the spirits of the recently deceased from the village to Safan, the land of the dead. The costumes are made in secrecy and are worn by relatives of the deceased. During the Jipae ceremony, which continues for weeks, the costumed dancers appear outside the ceremonial house and dance to the beat of drums for short intervals. At the end of the ceremony, the dancers are chased out of the village at dusk, never to be seen again, as the spirits go to Safan.

Atsj village in central Asmat has a large population, by Asmat village standards, of around 2000 people, for this reason, Atsj has always had an impressive men’s house with an extensive row of house posts. When the men’s house fell into disrepair the community mobilized to erect another, in 1989 the men’s house was replaced.

Today, there are two markets for Asmat art: the Western art market which looks for older, used pieces and carvings that are made along traditional lines; and the domestic Indonesian market which seeks objects that are aesthetically very different from those originally produced by the Asmat. The Indonesian market requires a symmetrical and polished look, and the carvings are made from hardwood, tables, and chairs with traditional Asmat designs, ashtrays, and other decorative items are made in abundance.

The 1990s saw an explosion in the creation and exportation of Asmat an around the world. While much of this art was of a low standard, there were still good artists producing art of great skill and beauty. Ritual carvings are the responsibility of the wow ipitsj, or expert carvers, and because these sacred items hold the spirit of their ancestors, they are made with much more reverence and care than those that are made for sale.

The Asmat’s desire for financial independence is the main reason for their making artifacts for sale. Artists often face the dilemma of whether to make one quality piece or several lesser pieces in the same length of time, with many artifact traders paying for quantity rather than quality. However, the Asmat will continue to make ritual carvings for themselves; in a transformed way their art and ceremony will continue. How can they not carve when their ancestors have been fashioned from wood and sung to life?

The Asmat people have faced many changes over the past forty years. Timber cutting and more recently the gathering of Agarwood or Kayu Gharu used in incense have affected their way of life. Whole villages are empty while the community spends more and more time in the forest looking for Agarwood or Kayu Gharu

While these industries have provided economic success, with them have come many of the problems experienced by indigenous communities around the world: degradation of the environment, poor health from smoking and the introduction of packaged food, and the effects of western consumerism.

While the financial benefits of carving are small in comparison with those gained by collecting Agarwood or Kayu Gharu the supplies will not last forever. When these resources are depleted perhaps there will be a new generation of Asmat artists who will take up carving, amazing the world with their insight into form and beauty.